“The wind on the sea bore a strange melody of an island that sings.” – Dora Sigerson

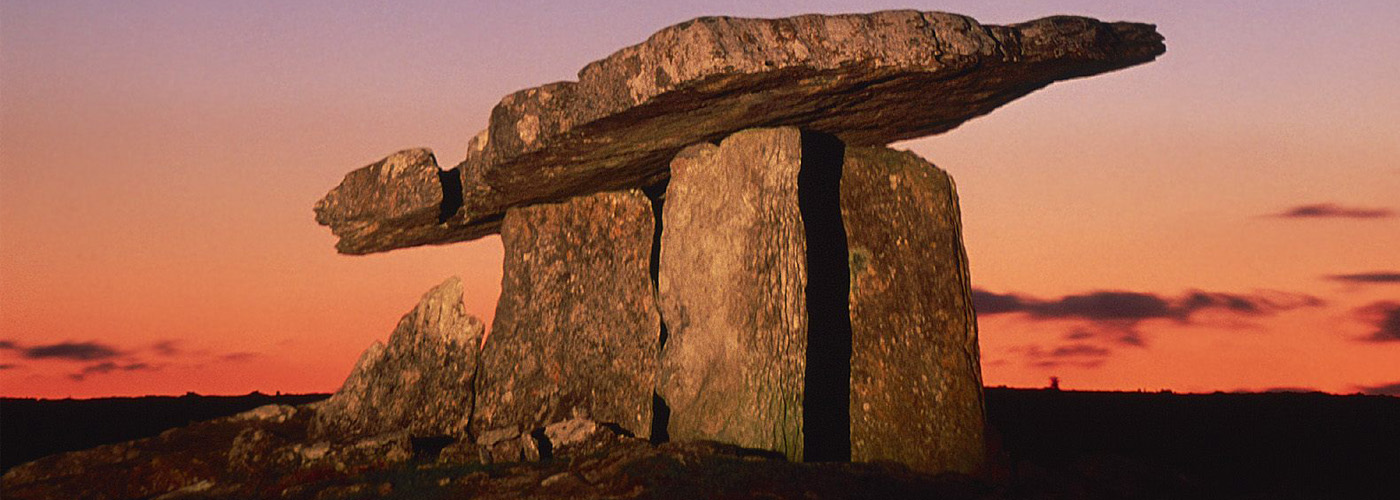

Celtic spirituality is based on a deep connection with the natural world. God is not a distant concept but a continual presence manifest in the whole of nature and deeply embedded in the world. For the ancient Celts, life itself was a ceremony, the whole of which was spiritually significant and magical. They considered the natural world divine and sensed the presence of their gods everywhere – in trees, rocks, rivers, bogs, and mountains.

These gods and goddesses were living forces of nature who reflected the earth’s majesty and expressed qualities such as inspiration, abundance, and eloquence. Celts worshipped their deities in woodland groves and near sacred water. Most sacred were the oak and mistletoe and no ritual was held without them. Druids were the teachers of wisdom and morality; a morality rooted in honour, family, and the sanctity of everyday life.

Central to Celtic spirituality was the belief in an immortal soul. Death was but another state of being, a transformation. Ancient Celts believed that alongside the ordinary world there existed a magical and mysterious realm called the Otherworld, a kind of Celtic heaven, the abode of the gods and the land of the dead. According to Celtic folklore, the Otherworld was the domain of a mythical race called the Túatha Dé Danaan, which means ‘the people of the goddess Danu’. They were Ireland’s original inhabitants descended from Danu, the mother goddess.

The Otherworld was a land of enchantment and contradictions accessible through lakes, caves, and fairy forts; a blissful place full of beauty, fine music, and delight; a place which held great treasures and brought inspiration to mortals who visited it. But it was also home to supernatural beings and monsters and a dangerous place to linger too long. At Samhain, our modern-day Halloween, the veil that concealed one world from the other became very thin allowing both the living and spirits to cross back and forth between the two realms. Holy sites of the ancient Irish, such as the Hill of Tara and Newgrange, were the dwelling places of the Celtic gods and the portals through which humans could enter the spirit world.

In the fifth century, a new religion arrived in Ireland in the form of Christianity. With its emphasis on love and individual salvation, the new faith preached by Saint Patrick, appealed to the Celtic spirit. Christianity adapted and absorbed many elements of the local religion allowing the Celtic people to embrace the new teaching while maintaining many of their ancient beliefs, customs, and practices. The Celtic church was more loosely organised than its Roman parent and operated, in many respects, outside the authority of the Roman church. Thus it avoided many of the conflicts and doctrinal wars that plagued Rome developing its own distinctive character – one that was more taken with the mystical.

A golden age of Celtic Christianity arose; it flowered in the form of independent monasteries that sprang up all over Ireland. Monks devoted themselves to lives of study, work, and prayer. The writing of books and gospels grew to become an exquisite art. By copying precious texts by hand, Celtic laws, annals, and myths were rescued from oblivion. Irish monasteries became renowned far-and-wide as sanctuaries of learning, and Ireland, enjoying a relative peace, was transformed into ‘the land of saints and scholars’.